MLZ is a cooperation between:

> Technische Universität München

> Technische Universität München > Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

MLZ is a member of:

> LENS

> LENS > ERF-AISBL

> ERF-AISBL

MLZ on social media:

MLZ (eng)

Lichtenbergstr.1

85748 Garching

19.11.2020

Neutrons detect air pollution

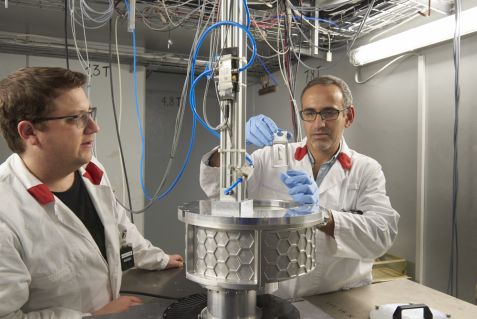

Dr. Nuno Canha (r.) analyzing his lichen in the prompt gamma activation analysis (PGAA) at the MLZ together with the instrument scientist Dr. Christian Stieghorst. © W. Schürmann / TUM

Portuguese scientists have analyzed lichens from areas with traditional charcoal production for the first time with the help of the Research Neutron Source Heinz Maier-Leibnitz (FRM II) of the Technical University of Munich (TUM). Lichens located near areas of charcoal production contained more than twice the concentration of phosphorus, which is generated during the combustion process.

In the region around Ponte de Sor (Portalegre County, Portugal), coal has been produced for centuries by smoldering wood in charcoal kilns. Traditional charcoal production not only provides jobs, it is also responsible for bad air quality.

Complaints about the smell, clouds of smoke in winter, reports of asthma and other respiratory diseases are not uncommon, says chemist Dr. Nuno Canha of the Instituto Superior Técnico of the University of Lisbon. However, no official air quality measurements have been taken up to date.

Lichens absorb pollutants from the air

The charcoal kilns emit the pollutants (1), which the lichens on the olive trees take up (2). Dr. Nuno Canha (r.) has analysed the linchens at the FRM II together with Dr. Christian Stieghorst (3). Art work: Reiner Müller. © André Moreira / visao (1), Dr. Nuno Canha (2), Wenzel Schürmann / TUM (3)

In the search for a method to measure air quality in a different way, Dr. Nuno Canha came across the Prompt Gamma Activation Analysis (PGAA), operating with neutrons of the Research Neutron Source FRM II in Garching. Here, the neutrons activate traces of pollutants, which can then be detected even in the smallest concentrations.

For his research, Dr. Canha collected lichens that grow on olive tree trunks in the area surrounding the charcoal ovens. Lichens are a symbiosis of fungi and algae without roots. “Because they absorb all their nutrients through the air, they are excellent indicators of air quality,” says Nuno Canha. He picked one batch in the spring and the other in the fall to eliminate seasonal differences.

More stress near the coal piles

One indicator for the exposure of lichens to air pollutants is their conductivity. The fine cell membranes break under extreme stress, which increases the conductivity of the lichens.

Nuno Canha found that lichens in the immediate vicinity of charcoal-producing ovens in the fall are twice as conductive as lichens located further from the ovens. In the spring, this difference between individual locations was not as noticeable.

The scientist suspects that this is due to the preceding rainy period before the lichens were picked in spring, which helps lower the plants’ stress levels. Before the lichen were picked in fall, it was rather dry on the other hand.

Other sources of pollution in the fall and spring

Together with TUM scientists Dr. Zsolt Révay and Dr. Christian Stieghorst, Nuno Canha identified 22 elements in the lichens using the Prompt Gamma Activation Analysis method.

What was particularly noticeable in the fall were the differences in the concentrations of the elements phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S), which are contained in the smoke of burning wood. The lichens that Canha collected in the immediate vicinity of charcoal ovens contained more than twice as much P in fall and the highest concentrations of S, compared to all other places.

“This fits in well with the conductivity measurements, which also attest higher stress to the lichens in the fall right next to the ovens,” says Canha. On the other hand, in spring, it was mainly the lichens near an inhabited area with little traffic that contained more sulfur and phosphorus. Nuno Canha attributes this to exhaust fumes from private wood-burning stoves and meteorological influences.

Nuno Canha hopes that the study will bring the impact of traditional charcoal production on air quality more into the authorities’ focus. Air filters could for example remove the pollutants from the exhaust gas.

Original publication:

Nuno Canha, Ana Rita Justino, Catarina Galinha, Joana Lage, Christian Stieghorst, Zsolt Revay, Célia Alves, Susana Marta Almeida. Elemental characterisation of native lichens collected in an area affected by traditional charcoal production. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 325:293–302 (2020). DOI:10.1007/s10967-020-07224-3

- The work was financed by the Portuguese Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

- Story on Nuno Canha’s research

- Film on the traditional charcoal kilns in Ponte de Sor

Contact:

Dr. Christian Stieghorst

Research Neutron Source

Heinz Maier-Leibnitz (FRM II) and

Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ)

Technical University of Munich (TUM)

Lichtenbergstr. 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

Tel.: +49 89 289-54871

E-Mail: christian.stieghorst@frm2.tum.de

Web: www.frm2.tum.de

MLZ is a cooperation between:

> Technische Universität München

> Technische Universität München > Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

MLZ is a member of:

> LENS

> LENS > ERF-AISBL

> ERF-AISBL

MLZ on social media: