MLZ is a cooperation between:

> Technische Universität München

> Technische Universität München > Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

MLZ is a member of:

> LENS

> LENS > ERF-AISBL

> ERF-AISBL

MLZ on social media:

MLZ (eng)

Lichtenbergstr.1

85748 Garching

3D printers in the service of science

Anyone who has seen the research neutron source FRM II knows that large machines and complex measuring instruments work here alongside the scientists who built them. A few hundred meters away from the large instruments, in a cube-shaped building, in a small office on the third floor, an ordinary 3D printer hums away.

Under his table, 100 kg of colorful thin plastic threads are stacked on spools. They are feeding the 3D printer. This so-called filament is special because it is manufactured specifically for the neutron source. It contains boron nitride, making it suitable as a neutron shield. This is because boron can absorb a neutron and then decays into harmless lithium, an α-particle, and some energy.

Boron swallows neutrons

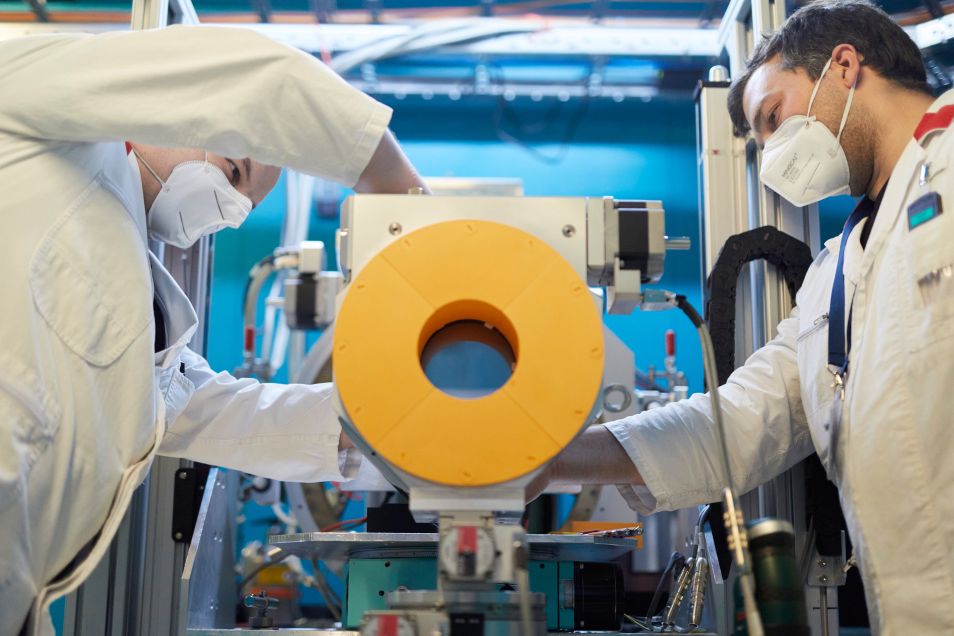

During measurements, it is particularly important that neutrons outside the detector surfaces do not hit the sensitive measuring instruments. This distorts the measurement or can even damage the measuring instruments. In addition, neutrons can activate metal components and thus increase the radiation exposure for the researchers. All this is prevented by shielding components that contain boron, for example. For instance, the bright orange shielding on the ANTARES instrument keeps the unwanted neutrons out and protects the metal component underneath.

The tireless FDM printer is used to manufacture the shield, because it’s cheaper to print with filament than to mill it from a block of solid material. “And the printer keeps working, even when we go home for the day,” adds Tobias Neuwirth, who helped develop the special filament.

3D printing falls under the term “additive manufacturing”. In this manufacturing method, the machine applies more material instead of removing it, as in milling. Here, the focus is specifically on fused deposition modeling (FDM), in which the printer melts a long plastic thread, or filament, through a nozzle and builds up a component layer by layer. The process can be seen in fast motion.

From adjustable shutter to Fermi chopper

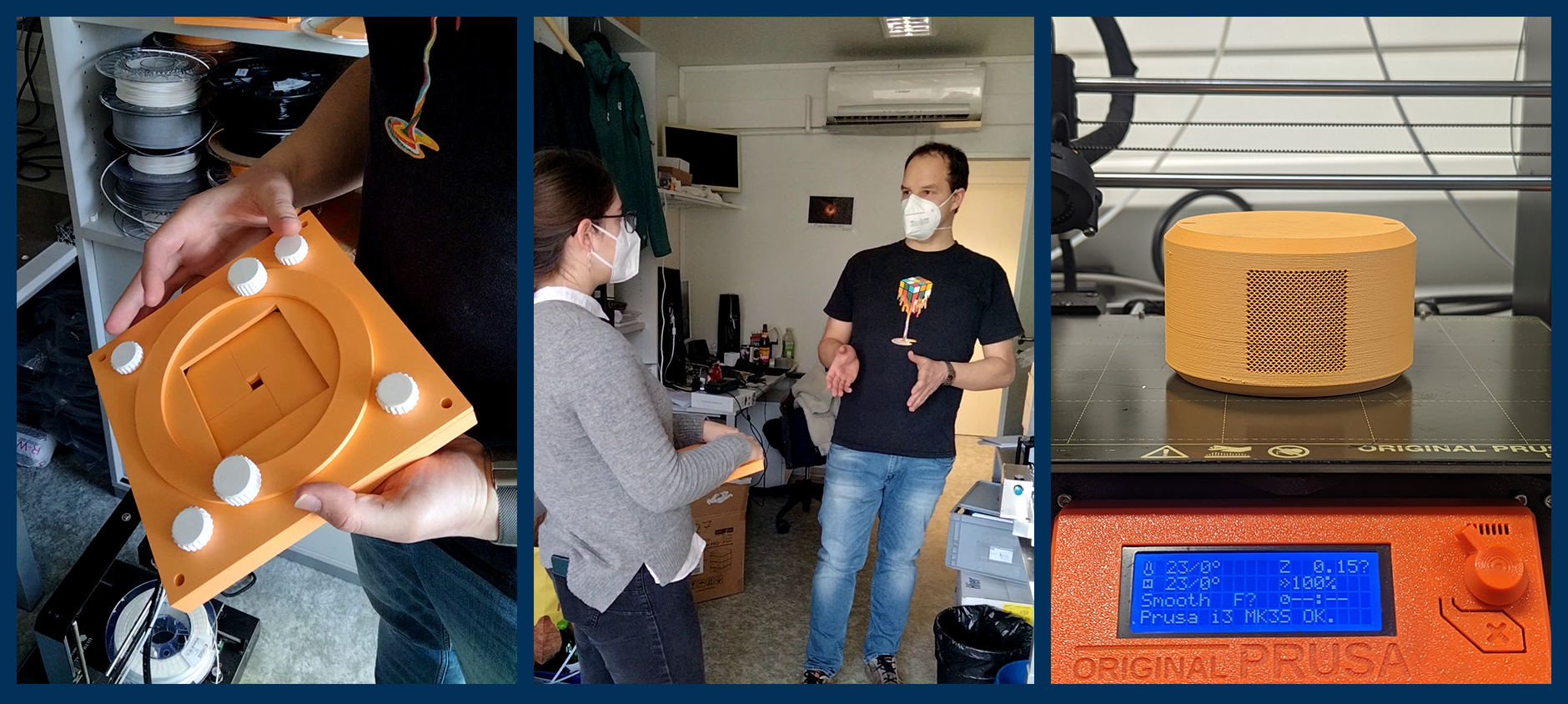

For an adjustable shutter, the printer went through about two days of printing. The shutter works like the shutter of a camera. Tobias Neuwirth enlarges and reduces the opening of the shutter by a rotary movement. “I designed it myself. I first had to learn how the closing mechanism works on a camera,” he explains. When used on the measuring instruments, the shutter can adjust the size of the neutron beam. This works in a similar way to the shutter on a camera, which reduces the incident light. In addition, the shutter opens and closes particularly smoothly. “This is due to the lubricating effect of boron nitride,” explains Neuwirth, who is doing his doctoral work at MLZ’s ANTARES radiography facility.

The shutter consists entirely of 3D-printed components and does not have the usual infill on the inside. To save filament, the 3D printer normally fills components with grid structures. Here at the neutron source, the components are filled with the borated plastic instead of the infill, because the more solid the shielding, the fewer neutrons get through.

3D prints for science

Tobias Neuwirth also shows a bright orange Fermi chopper that can be used to determine the neutron spectrum. The researchers make the heavy cylinder spin rapidly in the neutron beam, splitting it into short flashes. Then they measure the time it takes for the neutrons to travel from the chopper to the detector and use that to determine the energy of the approaching neutrons. The advantages of 3D printing are especially significant here: 684 delicate channels with a diameter of less than 1 mm run through the solid cylinder. It would not have been possible to manufacture the Fermi chopper as easily any other way.

Science is not just the ingenious discovery after an experiment. Science is building the measuring instrument for the experiment. Science is also constructing the shutter for the measuring instrument. And, of course, first of all, inventing the filament, which is stacked in rolls.

The 3D-printed shutter can be opened and closed particularly smoothly thanks to the boron nitride (l.). © FRM II / TUM Tobias Neuwirth explains the potential use cases of the special filament (M.). © FRM II / TUM The Fermi chopper made from the borated filament is ready in the print bed (r.). © Tobias Neuwirth, FRM II / TUM

Print it yourself: A neutron with spin sits on the model of the atomic egg. © Tobias Neuwirth FRM II / TUM

More Information:

A model of a neutron, which Tobias Neuwirth created in his spare time, can be downloaded here (LINK) and printed on your own 3D printer. License: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Contact:

Tobias Neuwirth

Technical University Munich

Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ)

Instrument ANTARES

Tel.: +49 89 289 11754

E-Mail: Tobias.Neuwirth@frm2.tum.de

Simon Sebold

Technical University Munich

Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (MLZ)

Instrument ANTARES

Tel.: +49 89 289 14641

E-Mail: Simon.Sebold@frm2.tum.de

Download of the printing files “Neutron on the atomic egg” as .stl

Elene Mamaladze

Presse- und Öffentlich-

keitsarbeit

FRM II

MLZ is a cooperation between:

> Technische Universität München

> Technische Universität München > Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

> Forschungszentrum Jülich

MLZ is a member of:

> LENS

> LENS > ERF-AISBL

> ERF-AISBL

MLZ on social media: